|

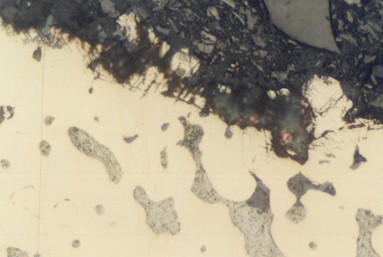

Detail of

corroded surface x500

Dr Peter

Northover’s analysis of the metal was by electron probe microanalysis using

wavelength dispersive spectrometry with varying magnifications up to a maximum of 500 x

(28). Dr Northover confirmed not only that the metal was old but that it had been in a

damp environment and was a heavily leaded gun metal and despite the different exterior

patina it was possible the two monkeys were exposed to the same corrosive environment.

This could well mean the surface condition of each monkey is original. There was limited

cold hammering at the surface. He suggested the metal was German or North West European

(29).

Dr Peter

Northover’s analysis of the metal was by electron probe microanalysis using

wavelength dispersive spectrometry with varying magnifications up to a maximum of 500 x

(28). Dr Northover confirmed not only that the metal was old but that it had been in a

damp environment and was a heavily leaded gun metal and despite the different exterior

patina it was possible the two monkeys were exposed to the same corrosive environment.

This could well mean the surface condition of each monkey is original. There was limited

cold hammering at the surface. He suggested the metal was German or North West European

(29).

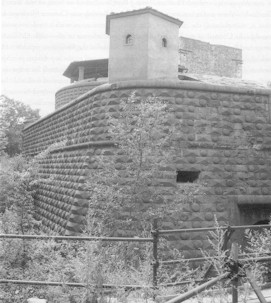

Recent research indicates that most of

Giambologna’s small bronzes tested so far are leaded bronzes. (Information provided

by V&A Sculpture Department.) At the time the monkeys were cast Giambologna did not

have his own foundry and there is documentary evidence that he used the metal of guns

captured by grand ducal forces and kept in guarded places like the Fortezza da Basso,

Florence (30).

Fortezza

da Basso

The fact that the metal is thought to be German or

North West European does not prevent the monkeys from being made in Italy, nor does it

mean the monkeys have to be made in Germany. The quality would seem to indicate that they

are not aftercasts. There is nothing to suggest that the monkeys are copies. It is well

documented that the Italians were importing copper from the Tyrol, Hungary, Thuringia,

Neusohl, (present day Banska Bystrica in Slovakia). According to Biringuccio (De La

Pirotechnia, Venice, 1540) the Italians had little or no copper of their own. (Information

kindly supplied by the V&A Sculpture Department.) The famous Fugger banking family

played a prominent role in the exploitation and export of copper.

Sculptors in bronze often sought advice from expert

gun founders on where to obtain copper, also on the quality and price. The equestrian

figure of Ferdinando I by Giambologna and Pietro Tacca was made of the metal of captured

Turkish guns (31). Turkey was known to import copper from South Germany across the

Mediterranean in Venetian ships) (32) and the equestrian figure of Cosimo I also by

Giambologna was probably made of Hungarian copper.

Ferdinando I

One of the finest representations of Florentine

metal work is to be found in the doors of the Baptistery, the famous Gates of Paradise by

Ghiberti (completed 1450) yet the metal is not Italian but was imported via Bruges and its

purchase is well documented (33). Attributions to country of manufacture cannot be deduced

by the origin of the metal. Particularly when there was such a large export trade.

Giambologna is known to have used gun metal and the

background to this is important. Italy in the first 60 years of the 16th

century was a war zone. Vast amounts of ordnance were brought in starting with Charles

VIII’s French invasion in 1494. Long standing dynastic claims was the usual excuse

(if excuse be needed) for all the many invasions but campaigning was the sport of Kings,

they enjoyed it. King Charles brought with him more guns than had ever been seen together

in Italy before. As a rule bronze guns when damaged or worn out could only be broken up

and recycled and the use of bronze was preferred over iron because bronze was a less

dangerous material and split rather than shattered. We can conclude there was copper alloy

available in large quantities from broken or worn out guns.

Cannon entering Italy came from all over Europe and

it is reasonable to assume the constituents varied. In 1550 there were gun foundries in

England, Sweden, Northern Germany, Low Countries, France, Spain, Portugal, Poland, Eastern

Adriatic, etc. If the foundry used by Giambologna used recycled gun metal with the guns

coming from different foundries and likely to vary in their constituents then it seriously

complicates attributions based on the make-up of the metal. Quite obviously the use of gun

metal makes statistical analyses useful but hard and fast conclusions of limited value.

Giambologna accepted the metal provided by patrons of which he could scarce know the

constituents (including gun metals) and much of his work was done by outside foundries.

Thus it is debatable how much control he had over the metal used in his bronzes. It

complicates the picture. The quality of an item under debate is possibly the best guide.

The metal comprises 13 different elements,

predominantly copper of course, but also including gold and silver. Copper can contain

gold and silver and this is a pointer that the metal could be old. (34)

It seems that most Giambologna small bronzes tested

so far have been leaded bronzes. The addition of high levels of lead would probably be

intentional to take advantage of the properties of lead to lower the melting point of the

alloy (m.p. of lead is 327.4°c) and to improve the flowing properties so as to help fill

the mould. Lead gives a duller colour to the alloy and makes easier the work of chiselling

and planishing during the finishing process. The isotopic composition of lead in copper

alloys may give clues as to origin. The scientists hold out possibilities of further

information. (35) The addition of lead and zinc not only lowers the melting point, but

reduces the shrinkage of cast bronze.

Gun metal was usually 90% copper, 10% tin, but some

foundries added latten, a mixture of copper, zinc and lead, to give a better colour. As

the monkeys are a gun metal and an attractive red-brown colour this might account for the

zinc content. In the 1550 edition of Vasari’s Lives it is stated that for bronze

statuary the proportion of metal was two thirds copper to one of brass (brass is an alloy

of copper and zinc). The zinc content of the monkeys is 5.63% and 5.88% but zinc seems to

be a fugitive element, tending to evaporate rapidly in some quantity and oxidate if the

fusion is not done correctly. There has to be a reducing atmosphere. After all the melting

point of zinc is 418 degrees centigrade and the melting point of copper is 1083 degrees

centigrade. The element zinc itself was not isolated as a pure metal until the mid 18th

century. (36)

The inclusion of trace elements in the metal –

gold, silver, nickel, arsenic, cobalt, etc, does not prove the metal is old but with the improved and sophisticated refining techniques in the

19th / 20th centuries points at least in this direction. The

percentage of arsenic might have been intentional as it could have been used as a

hardening agent in the alloy even in small quantities (37). Also present in the metal is a

small amount of antimony, also a hardening agent. The book published in 1556 by Georgius

Agricola, De Re Metallica (reprinted 1950) gives an unprecedented wealth of material on

mining, refining, smelting, etc.

The scientists hold out possibilities that the

patterns of trace elements in metal alloys can provide finger prints capable of

distinguishing artefacts made in one region from those made in another but the use of gun

metal by Giambologna will obviously be a complicating factor.

For the monkeys to be of a 16th century

date and to enable repeat casts to be made they would normally be cast by the lost wax

process using re-usable piece moulds and not the lost wax process where the original model

is lost. Most of the evidence of the use of piece moulds has been removed but traces of

the seams remain especially on the base. (38)

X-radiographs taken by Dr Brian Gilmour at HM

Armouries, Tower of London, reveal evidence of numerous discs, probably the cut-off

runners and risers (sprues). Also "plugged" square holes from the use of square

core pins or chaplets, which hold the core in place when the wax is melted out are

present. They also reveal patched casting flaws and a wire armature in the tail of one

monkey. Giambologna is known to have used wire armatures to give support to the structure

of the core and they also acted as core pins. Sometimes short pieces of wire were used to

strengthen isolated sections of the core. The trace elements of iron may have come

from these wire armatures.

Evidence of lost wax process (3 images)

It is a

characteristic of Giambologna’s workshop practice to use square core pins and there

is evidence of this, as mentioned, in the bronze Mercury in the Museo Civico, Bologna,

1564, and also in the famous Turkey attributed to Giambologna in the Bargello Museum,

Florence, where some of the plugs seem to have fallen out leaving square holes. The metal

cast of the monkeys is fairly thin and the colour of the metal is what was often seen in

the 16th century, a coppery red. The precision and quality of the casting of

these two monkeys must be left to the eye of the individual viewer. Dr Gilmour formerly at

HM Armouries, Tower of London, agreed that the metal was likely to be old.

|